This episode of CS is titled, Luther’s Struggle.

As we saw last time, Luther’s situation after appearing before Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms didn’t look hopeful. The majority of officials there decided to apply the papal bull excommunicating Luther and removing his protection. Some of the nobles knew they could incur the Pope’s favor by taking matters into their own hands and assassinating the troublesome priest. But the German prince Frederick the Wise, one of the Emperor’s most important supporters, arranged to air-quotes à “kidnap” Luther on his way back to Wittenberg. He secreted Luther to his castle at Wartburg under an assumed identity. Now in hiding, Luther used the time to translate the NT from Greek into a superbly simple German Bible. He finished it in the Fall of 1522 and followed it up with an OT translation from Hebrew. This took longer and wasn’t finished till 1534. The completed Bible proved to be no less a force in the German-speaking world than the King James Version was later to be in the English sphere, and it’s considered one of Luther’s most valuable contributions.

The revolt against Rome sparked by Luther’s list tacked to the castle church door at Wittenberg began to spread. In town after town, priests and town councils removed statues from churches and abandoned the Mass. More priests and monks stepped forward, adding their voice to the call for reform, many more radical than Luther. More importantly, an increasing number of civil officials decided to back Luther in defiance of the Emperor and Pope.

By 1522, it was clear to Luther he could safety return to Wittenberg and put into practice the reforms he was convinced the Church needed to install. What he did there became the model for a good part of Germany. He abolished the office of bishop because he couldn’t find it in Scripture. Local churches needed pastors who were servants, not a religious royalty.

During his time at the Wartburg, Luther gave much thought to the issue of celibacy. He wrote a tract called On Monastic Vows where he expounded on the idea that a sequestered life wasn’t really Biblical. When he returned to Wittenberg, he dissolved the monasteries and ended clerical celibacy. The resources of the monasteries were used to relieve the poor, and marriages between former celibates became the order of the day. Erasmus noted that the tragedy of the break with Rome looked like it would finish as a comedy; with everyone married and living happily ever after.

Luther himself took a wife in 1525, the former nun, Katherine von Bora. The story goes she was an eminently practical woman but not all that attractive. When her fellow sisters got married, she was left single and approached Luther, saying it was his fault she was now alone and without support. She suggested it was his duty to remedy her situation. When he asked how he as supposed to do that, she replied marrying her was his best option. So he did.

A new image of full-time ministry appeared in western Christianity—the married pastor living like any other man with his own family. Luther later wrote, “There is a lot to get used to in the first year of marriage. One wakes up in the morning and finds a pair of pigtails on the pillow which were not there before.” By all accounts, while Martin and Katherine’s marriage began as a purely pragmatic arrangement, the love between them grew into a rich joy. Luther was deeply affectionate to his wife, who often was instrumental in keeping Luther’s frequent dark moods from overwhelming him. They had six children.

Martin and Katherine lived in what had been the Augustinian convent. Their house was nearly always full of guests who enjoyed sitting at their table. Some of his students the Luthers had in for meals took down their conversation, now published in a work called Table Talk.

Luther understood if Reform was to take root and grow, it had to be fueled by the study of the Bible. Studying Scripture required the ability to read it and to reason logically. So he placed a great emphasis on education and urged parents to send their children to school. To assist in the education of youth, he composed a Large Catechism in 1528, then a more popular Small Catechism a year later. In the Small Catechism, Luther gave a simple exposition of the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the two sacraments. He offered forms for confession, morning and evening prayers, and grace at meals.

Keep in mind Luther hadn’t begun in 1517 with a fully developed theological position and a plan to Reform the Roman church or break away and start a separate religious franchise. That was nowhere on the horizon. When he tacked his list on Wittenberg’s church door, it was simply a reflection of his desire that church officials begin examining both long-held traditions and more recent innovations by holding them up to the light of Scripture. As things progressed, Luther realized he had to follow his own advice.

Many Protestants have heard of Luther’s 95 Theses but they’ve not read them. It’s surprising to see what he calls for people to examine there. Turns out, there’s little in Luther’s List that ended up in the core doctrines of the Reformation. But once Luther embraced the principle of reviewing everything in the light of God’s Word, a far more complete doctrinal picture began to take shape. He saw his way clear in the matter of justification by grace thru faith. When he applied this to the issue of indulgences is when he popped up on Rome’s radar. His emerging understanding of the priesthood of all believers was a threat Rome couldn’t ignore because it threatened their religious hegemony. Soon, everything was being scrutinized in the light of Scripture.

Luther translated the Latin liturgy into German. People began receiving Communion in both bread and wine. The emphasis in church services switched from the celebration of the Mass to the preaching and teaching of God’s Word.

In 1524, Germany got a taste of how far reaching Luther’s call for reforms could reach. His insistence that church and society follow the commands of Scripture led to an uprising of the peasants against the nobility. The people applied the concept of the freedom of the Christian to the economic and social spheres. Long kept under the domineering thumb of the nobility, the peasants revolted against their feudal lords. They demanded an end to medieval serfdom, unless it could be justified from the Bible, and relief from the excessive services demanded of them which kept them in virtual slavery.

At the beginning of their protest, Luther agreed with the peasants and recognized the justice of their complaints. What he stridently warned against was the use of violence to enforce their will on a recalcitrant nobility. When violence did break out, he lashed out against the peasants. Since the printing press was already a major part of his work, he employed it again and wrote a pamphlet titled, Against the Thievish and Murderous Hordes of Peasants. In it, Luther called on the princes to “knock down, strangle, stab … and think nothing so venomous, pernicious, or Satanic as an insurgent.”

In 1525, the nobles crushed the revolt at a cost of some 100,000 lives. The survivors now called Luther a false prophet. Many of them returned to Catholicism or turned to more radical forms of the Reformation.

Luther’s conservative political and economic views devolved from his belief that the equality of all men before God applied to spiritual rather than secular matters. Though these views alienated the common people, they proved a boon to Luther’s influence with the German princes, many of whom became Lutheran in part because Luther’s views allowed them to control the Church in their territories, thereby strengthening their power and wealth.

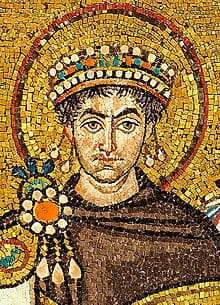

In 1530, a conference of Reformation leaders convened in Augsburg to draw up a common Statement of Faith. The leadership of the movement had already begun to move beyond Luther. He was still an outlaw and unable to attend. So the task of presenting Luther’s ideas fell to his colleague, a young professor of Greek at Wittenberg, Philip Melanchthon. The young scholar drafted the Augsburg Confession signed by Lutheran princes and theologians. And though a growing movement of the German nobility now threw their weight behind the Reform, Emperor Charles V, who depended on their support, was no more inclined to join the movement than he’d been a Worms.

After 1530, Charles made clear his intention to crush the growing heresy. The Lutheran princes banded together in 1531 in the Schmalkald League, and between 1546 and 55 there was scattered, on-and-off-again civil war. The combatants reached a compromise in the Peace of Augsburg, which allowed each prince to decide the religion of his subjects, with the only acceptable options being Lutheran or Catholic, and ordered all Catholic bishops to give up their property if they turned Lutheran.

The effects of this treaty were profound. Lutheranism became a State religion in large portions of the Empire. It spread north to Scandinavia. Religious opinions became the private property of princes, and individuals had to believe what their prince chose.

Luther remained engaged in unending debate with the Roman Church. And it wasn’t long before he found himself embroiled in disagreements with other reformers. Outspoken and combative, he often collided with equally fierce opponents. These controversies took on a bitter edge that saw Luther hurling vicious epithets at his opponents. The insults he’d once used for the Pope were turned on fellow Reformers. All this greatly hampered reform.

For example, Luther became entangled in a controversy with the humanist scholar and reformer Erasmus. The two had much in common, sharing concerns for scholarship, for opening up the Scriptures, and for doctrinal and practical reform. Still, they differed sharply in character and theological approach. Under pressure to declare himself either for Luther or against him, Erasmus turned to the important issue of the freedom of the will and published a work titled, Diatribe on Free Will in 1524. To this Luther made a scornfully sharp reply a year later in his Bondage of the Will. This work is a powerful statement of the Augustinian position that in matters of righteousness and salvation human will has no power to act apart from God’s enabling grace. Erasmus replied to Luther’s reply, but Luther ignored it. Erasmus then aligned himself with opponents of the Reformation, although still urging reform and maintaining friendly relations with other reformers.

The Lutherans themselves experienced a split over how to understand Communion. Like a bulldog, Luther clung to the words of Jesus “This is my body” as supporting his belief that Jesus was present in the elements. When the Southern Germans and Swiss broke away saying that the elements were meant ot be understood as symbolic, Luther published a couple of scathing responses in 1526 and 7. There’s a coarseness to his style in the second of these that may indicate Luther had no desire to win his opponents, only to insult them.

Since this is a history and not theology podcast, I’m not going to go into all the nuances of the Eucharistic debate that ensued between the Lutherans and other Reformers. Suffice it to say, it became one of the major issues of controversy between them.

Luther ran into other difficulties, too.

He hoped at first that the renewing of the Gospel would open the way for the conversion of the Jews. When that didn’t pan out, he made virulent attacks on them, planting a deep stain on his record. Philip of Hesse, a champion of the Reformation, became an embarrassment to Luther when he gave assent to Philip’s bigamous marriage in 1540. The development of armed religious alliances in the empire worried Luther, for while he accepted the divine authorization of princes and valued their help in practical reformation, he struggled hard for the principle that the Gospel does not need to be advanced or defended by military power. He was spared the conflict that came so soon after his death.

Even his sympathetic biographers have found it hard to justify some of Luther’s actions in his declining years. By the time of his death in 1546, says biographer Roland Bainton, Luther was “an irascible old man, petulant, peevish, unrestrained, and at times positively coarse.” As chance would have it, his schedule brought him to Eisleben, the town of his birth, where he died on Feb. 18, 1546.

Fortunately, the personal defects of an aging rebel don’t in any way detract from the greatness of Luther’s achievements, which transformed not only Christianity but Western civilization. He took four basic concerns and offered vital new answers.

To the question – How is a person saved, Luther replied: not by works but by faith alone.

To the question – Where does religious authority lie, he answered: not in the visible institution called the Roman church but in the Word of God found in the Bible.

To the question—What is the church?—he responded: the whole community of Christian believers, since all are priests before God.

And last, to the question—What is the center of the Christian life?—he replied: serving God in any useful calling, whether ordained or not.