This episode is titled, Dominic and continues our look on monastic life.

In our last episode, we considered Francis of Assisi and the monastic order that followed him, the Franciscans. In this installment, we take a look at the other great order that developed at that time; the Dominicans.

Dominic was born in the region of Castile, Spain in 1170. He excelled as a student at an early age. A priest by the age of 25, he was invited by his bishop to accompany him on a visit to Southern France where he ran into a group of supposed-heretics known as the Cathars. Dominic threw himself into a Church-sanctioned suppression of the Cathars through a preaching tour of the region.

Dominic was an effective debater of Cathar theology. He persuaded many who’d leaned toward their sect to instead walk away. These converts became zealous in the resistance against them. For this, the Bishop of Toulouse gave Dominic 1/6th of the diocesan tithes to continue his work. Another wealthy supporter gave Dominic a house in Toulouse so he could live and work at the center of controversy.

We’ll come back to the Cathars in a future episode.

Dominic visited Rome during the 4th Lateran Council, the subject of another future episode. He was encouraged by Pope Innocent III in his apologetic work but was refused in his request to start a new monastic order. The Pope suggested he instead join one of the existing orders. Since a Pope’s suggestion is really a command, Dominic chose the Augustinians. He donned their black monk’s habit and built a convent at Toulouse.

He returned to Rome a year later, staying for about a half year. The new Pope Honorius II granted his petition to start a new order. Originally called the “Order of Preaching Brothers,” it was the first religious community dedicated to preaching. The order grew rapidly in the 13th C, gaining 15,000 members in 557 houses by the end of the century.

When he returned to France, Dominic began sending monks to start colonies. The order quickly took root in Paris, Bologna, and Rome. Dominic returned to Spain where in 1218 he established separate communities for women and men.

From France, the Dominicans launched into Germany. They quickly established themselves in Cologne, Worms, Strasbourg, Basel, and other cities. In 1221, the order was introduced in England, and at once settled in Oxford. The Blackfriars Bridge, London, carries in its name the memory of their priory there.

Dominic died at Bologna in August, 1221. His tomb is decorated by the artwork of Nicholas of Pisa and Michaelangelo. Compared to the speedy recognition of Francis as a saint only two years after his death, Dominic’s took thirteen years; still a quick canonization.

Dominic lacked the warm, passionate concern for the poor and needy that marked his contemporary Francis. But if Francis was devoted to Lady Poverty, Dominic was pledged to Sir Truth. If Francis and Dominic were part of a cruise ship’s crew; Francis would be the activities director, Dominic the lawyer.

An old story illustrates the contrast between them. Interrupted in his studies by the chirping of a sparrow, Dominic caught and plucked it. Francis, on the other hand, is revered for his tender compassion and care for all things. To this day he’s represented in art with a bird perched on his shoulder.

Dominic was resolute in purpose, zealous in propagating Orthodoxy, and devoted to the Church and its hierarchy. His influence continues through the organization he created.

At the time of Dominic’s death, the preaching monks, or “friars” as they were called, had sixty monasteries and convents scattered across Europe. A few years later, they’d pressed to Jerusalem and deep into the North. Because the Dominicans were the Vatican’s preaching authority, they received numerous privileges to carry out their mission any and everywhere.

Mendicancy, that is begging as a means of support, was made the rule of the order in 1220. The example of Francis was followed, and the order as well as the individual monks renounced all right to personal property. However, this mendicancy was never emphasized among the Dominicans as it was among Franciscans. The obligation of corporate poverty was revoked in 1477. Dominic’s last exhortation to his followers was that they should love, service humbly, and live in poverty but to be frank, those precepts were never really taken much to heart by most of his followers.

Unlike Francis, Dominic didn’t require manual labor from the members of the order. He substituted study and preaching for labor. The Dominicans were the first monastics to adopt rules for studying. When Dominic founded his monastery in Paris, and sent seventeen of his order to staff it, he told them to “study and preach.” A theological course of four years in philosophy and theology was required before a license was granted to preach, and three years more of theological study followed.

Preaching and the saving of souls were defined as the chief aim of the order. No one was permitted to preach outside the cloister until he was 25. And they were not to receive money or other gifts for preaching, except food. Vincent Ferrer and Savonarola were the most renowned of the Dominican preachers of the Middle Ages. The mission of the Dominicans was mostly to the upper classes. They were the patrician order among the monastics.

Dominic would likely have been just one more nameless priest among thousands of the Middle Ages had it not been for that fateful trip to Southern France where he encountered the Cathars. He’d surely heard of them back in Spain but it was their popularity in France that provoked him. He saw and heard nothing among the heretics that he knew some good, solid teaching and preaching couldn’t correct. He was the right man, at the right time doing the right thing; at first. But his success at answering the errors of the Cathars gained him support that pressed him to step up his opposition toward error. That opposition would turn sinister and into what is arguably one of the dark spots on Church history – the Inquisition. Though hundreds of years have passed, the word still causes many to shiver in terror.

Dante said of Dominic he was, “Good to his friends, but dreadful to his enemies.”

We’ll take a closer look at the Inquisition in a later episode. For now à

In 1232, the conduct of the Inquisition was committed to the care of the Dominicans. Northern France, Spain, and Germany fell to their lot. The stern Torquemada was a Dominican, and the atrocious measures which he employed to spy out and punish ecclesiastical dissent an indelible blot on them.

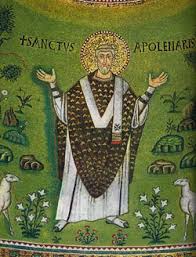

The order’s device or emblem as appointed by the Pope was a dog with a lighted torch in its mouth. The dog represented the call to watch, the torch to illuminate the world. A painting in their convent in Florence represents the place the order came to occupy as hunters of heretics. It portrays dogs dressed in Dominican colors, chasing away heretic-foxes. All the while the pope and emperor, enthroned and surrounded by counselors, look on with satisfaction.

As we end this episode, I thought it wise to make a quick review of the Mendicant monastic orders we’ve been looking at.

First, the Mendicant orders differed from previous monastics in that they were committed, not just to individual but corporate poverty. The mendicant houses drew no income from rents or property. They depended on charity.

Second, the friars didn’t stay sequestered in monastic communes. Their task was to be out and about in the world preaching the Gospel. Because all of European society was deemed Christian, the mendicants took the entire world as their parish. Their cloister wasn’t the halls of a convent; it was the public marketplace.

Third, the rise of the universities at this time presented both the Franciscans and Dominicans with new opportunities to get the Gospel message out by educating Europe’s future generations.

Fourth, the mendicants promoted a renewal of piety by the Tertiary or third-level orders they set up, which allowed lay people an opportunity to attend a kind of monk-camp.

Fifth, The mendicants were directly answerable to the Pope rather than local bishops or intermediaries who often used orders to their own political and economic ends.

Sixth, the friars composed an order and organization more than a specific house as the previous orders had done. Before the mendicants, monks and nuns joined a convent or monastery. Their identity was wrapped up in that specific cloister. The Mendicants joined an order that was spread over dozens of such houses. Monks’ obedience was now not to the local abbot or abbess, but to the order’s leader.

Besides the Dominicans and Franciscans, other mendicant orders were the Carmelites, who began as hermits in the Holy Land in the 12th C; the Hermits of St. Augustine, and the Servites, who’d begun under the Augustinian rule in the 13th C, but became mendicants in the 15th.