The episode is titled Why So Critical?

Two episodes back we introduced the themes that would lead eventually to Theological Liberalism. The last episode we talked a bit about how the church, mostly the Roman Catholic church, pushed back against those themes. In this episode, we’ll go further into the birth of liberalism.

The 20th century was unkind to Theological Liberalism, with its shining vision of the Universal Brotherhood of Man under the Universal Fatherhood of God. Yet, many mainline Protestant denominations still hold solidarity with Liberalism. It was Professor Sydney Ahlstrom’s view that liberals had provoked as much controversy in the 19th century as the Reformers did in the 16th. The reason for that controversy lay in their objective, stated by one of its premier advocates and popularizers – Harry Emerson Fosdick. In his autobiography, The Living of These Days, the influential pastor of the famous Riverside Church in New York City, said the aim of liberal theology was to make it possible “to be both an intelligent modern and a serious Christian.”

Liberals hoped to address a problem may be as old as The Faith itself: That is, how can Christians reconcile their faith to the intellectual climate of their time without compromising the Essentials of The Gospel? By the evaluation of modern Evangelicals, Liberalism failed in that quest precisely because they DID compromise those essentials in their desire to be relevant among their unbelieving peers. Richard Niebuhr expressed the irony of theological liberalism when he said in liberalism “a God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.”

Personally, I’ve been reluctant to produce this episode because the more I’ve studied Theological liberalism, the less certain of being able to handle it competently I’ve grown. Definitions for it are no easier than for political liberalism. In fact, many deny that Protestant liberalism is a theology at all. They refer to it as an “outlook,” or “approach.” Henry Coffin of Union Seminary described liberalism as a “spirit” that honors truth so supremely and it craves the freedom to discuss, publish, and pursue what it believes to be true.

But then, if THAT is true, it must certainly lead to certain convictions that derive values and produce judgments. And THAT is precisely what we see the history of Protestant liberalism producing.

In the words of Bruce Shelley, “Liberals believed Christian theology had to come to terms with modern science if it ever hoped to claim and hold the allegiance of intelligent men.” So liberals refused to accept religious beliefs on authority alone. They insisted faith must submit to reason and experience. Following the thinking of the Enlightenment, of which they were the spiritual children, they claimed the human mind was capable of thinking God’s thoughts after Him. So, the best insight into the nature and character of God wasn’t His self-revelation in Scripture, which smacked of the old authoritarianism they eschewed; it was human intuition and reason.

By surrendering to what we’ll call “the modern mind” liberals accepted the assumption of their time that the universe was a massive but synchronized machine, like a well-made watch. The key to this machine was Unity.

I’ll come back to that in a moment, but a little editorializing seems in order. And while some may be rolling their eyes, I think this is germane to what this podcast is – a review of History – specifically Church History. I just made reference to “the modern mind.”

Modern is another term that has multiple meanings. Historians use it to refer to the Modern Era, which they debate over the time span of, but let’s go with the common view that it runs from about 1500 to 1900-ish. So wait! IF the Modern Era ended at the beginning of the 20th century, what Era are we in now? The Atomic or Nuclear Era, the Post-Modern Era, the Information Age? Different labels get assigned to the current historical epoch. But don’t we still refer to current trends and fashions as being “modern”? Aren’t we “moderns” in the sense that we’re living NOW? Not many people would want to be considered not modern.

It gets confusing because the word modern is plastic with a lot of different meanings and connotations. But here’s where it adds to the confusion as it relates to our discussion on theological liberalism, and some of this spills over into political liberalism. There was a desire to accommodate Christian theology to the modern mind. By which emerging liberals meant accepting the findings of “modern science” as (air-quote) fact and making theology fit into those supposed facts. But there’s a difference, a vast difference between facts and interpretations of facts. A few years after a so-called “Fact” was established by science, others came along to say, “Yeah, uh, we weren’t quite right about that. It’s actually this.” And, it wasn’t uncommon for even that revised new paradigm to be revised yet again.

Is coffee good or bad for you? Right now, it’s good. But wait a month and it’ll be bad again, But not to worry, a year out, coffee will be the key to long life and amazing prosperity. Okay. I exaggerate, but not by much.

My point is this, the current moment, what we mean by at least ONE of those definitions of “modern” – has a nasty habit of thinking that just by virtue of the fact that we’ve progressed to this point, we’re now smarter, more enlightened and so better than all the moments before this. There’s a kind of arrogance that seems endemic to the fact that we’re here now – the most evolved and educated class of human beings history has known.

But a few moments from now, the people living then will think the same thing about themselves and see us as unenlightened bores. And the modern mind will have moved on to the new so-called facts of what turns out to not be science but is in truth scientism.

When theology is hitched to “the modern mind” as liberals aimed to do, its eternal verities are traded in for the changing whims of what that is now, and now, then now. And we have to unhitch the adjective ‘eternal’ from those verities – because they simply aren’t true any longer.

Okay, end of the editorializing. Adopting the modern view that the universe was a vast harmonious machine, liberals aimed for Unity. They tried merging revelation with natural religion and Christianity with other religions by looking for common themes. Thus, the study of comparative religions was born as an academic pursuit. They aimed to lower the wall between those who were saved and the lost, between God and man.

Liberals regarded the traditional and orthodox belief in a transcendent God who exists in a realm above and beyond the natural as stalling their agenda to unify and harmonize. They blurred the lines between the natural and supernatural and equated the spiritual realm with human consciousness. The spiritual realm became little more than the intellectual and emotional activity of human beings. And God was defined as the universal life force that even now is creating the Universe. One liberal said it this way, “Some call it evolution; others call it God.”

Remember, theological liberals, aimed to harmonize science with faith. The newest darling on the scientific scene was Darwin and his emerging theory of everything – Evolution by Mutation and Natural Selection. Theological Liberalism had no problem accepting Darwin’s theory.

While the challenge of some of the assertions of science to orthodox Christianity was serious, they were secondary to the new views of history. Those views were adopted from the scientific method, which began a rigorous review of the assumptions that had framed classical or traditional history. If facts are based on evidence and repeatable observations, what were we to do with history, which by its very nature refers to the past? Historical criticism became the framework for a new generation of historians and academics. If a defendant is considered innocent until proven guilty in a court of law, events regarded by traditional history as certain were now suspect until proven true. Modern sensibilities were read back into and layered over persons and events of the past.

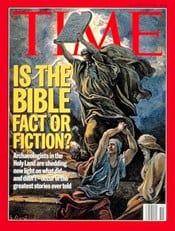

The application of these liberal principles of historical inquiry to the Bible was called “biblical criticism.” But don’t understand the term criticism here to be pejorative. Biblical criticism simply meant a study of Scripture in order to discover its real meaning. But Biblical criticism discarded the dogmatics of traditional inquiry in favor of a more rationalistic approach.

Biblical criticism flowed into two streams, lower and higher criticism. The low-critic dealt with the problem of the physical manuscripts and codices. Their goal was to find the earliest and most reliable texts of Scripture, as close as possible to the originals. The work of lower criticism helped produce the large number of New Testament manuscripts we have today and assisted translators in the work of producing modern Bible versions.

Higher criticism proved to be a very different matter. The high-critic wasn’t so much interested in the accuracy of the text. He was more concerned with the meaning of the text. To get at that meaning, he often read between the lines or went behind the text to the events assumed to have produced it. This meant discovering who wrote it, when, and why. Higher criticism held that we can only get at the meaning of a passage when we see it against its background. Higher critics then went to work, systematically dismantling traditional views regarding hundreds of passages. A beloved Psalm, attributed in the text itself to David, higher critics tell us wasn’t written by King D. All because it has a word scholars say wasn’t used for forty-two years after David. So, it must have been written by the Jews in exile.

The methods of Biblical higher criticism weren’t new. They’d been in use for a while on other ancient texts. But during the 19th century, they were applied to the Bible. And for many liberals, all it took was some scholar with a Ph.D. to say a traditional view of a passage was wrong, it was this other thing, for them to categorically throw over tradition in favor of the new view.

Higher criticism agreed generally that Moses didn’t write the Pentateuch as both Jews and Christians had universally agreed till then. Instead, they’d been penned by at least four authors. And passages that seemed to be prophetic of future events must have been written after the events they supposedly foretold because modern scientific sensibilities don’t allow for the supernatural. High-critics said the Gospel of John, wasn’t = John’s Gospel, that is.

Diverging from the discipline of Biblical Criticism was what’s known as the search for the “historical Jesus.” Liberals like the idea of Jesus, if not the actual Jesus presented in the Gospels. You know, the One Who made a whip and cleared the temple and called people white-washed tombs. A liberal reforming Jesus was someone they could get behind, but not the substitutionary-atoning Jesus of the Epistles because THAT Jesus meant a Holy God whose justice demands a sacrifice to discharge sins. And that was an archaic idea no longer acceptable to modern sensibilities. So, liberal critics assigned themselves the mission of saving Jesus from such barbaric and outdated modes of thinking. They assumed the early church and writers of the Gospels embellished Scripture to that end. It was their task to sift through the text and pull out what was legitimate and what was bogus.

Literally dozens of so-called “lives of Jesus” were written during the 19th century, each claiming it revealed the true, historical Jesus. While most contradicted each other, they nearly all agreed to disavow the miraculous was central to the genuine Jesus story. They were bound to this since “science” proved the impossibility of miracles.

Quick editorial comment – Let’s be clear, the scientific method can’t prove miracles are impossible. Miracles are by their very definition outside the realm of scientific investigation because repeatability is one of the required elements of the scientific method. Miracles, by the very definition, are a contravention of the laws that govern the material realm, and AREN’T typically repeatable. Miracles are unexpected!

In their quest to merge science and faith, liberal theologians allowed the so-called facts of their time to be the filter through which they re-worked the content of the Christian Faith. They said Jesus not only didn’t work miracles, He never claimed to be the Messiah, or that history would climax in His visible return to establish the kingdom of God.

The cumulative effect of all this was the doubt cast on the Bible as the inspired and infallible Word of God as the authority for faith and practice.

When higher critics were done, Liberals were free to sort through Scripture to pick and choose what they wished. They read the Bible through the filter of evolution and saw a progression from blood-thirsty deities requiring sacrifices, to the Jews who embraced the idea of a righteous God served by those who pursue justice, love mercy, and walk humbly. This progressive revelation of God reached its climax in Jesus, where God is portrayed as the loving Father of all Humanity.

So far, our review of Theological Liberalism has seemed bent toward a tearing down of traditionalism. That looks at just one side of the liberal coin. The other side was the concurrent movement known as Romanticism.

During the early 19th century, Romanticism was a movement that flowed mainly in the artistic and intellectual communities. It looked at life through feelings. The Industrial Age seemed to many to reduce man to a cog in a vast societal machine. Romanticism was an attempt to lift man out of the gears and set him down as a glorious creator and engineer. Man was evolution’s apex achievement and had every right, duty even, to exalt in his lofty place, as well as to aspire to even greater heights. Romanticism focused on the individual and his/her ambitions to attain their ultimate potential. This was the genesis of the Human Potential Movement.

So on one hand, liberals aimed for unity, but Romanticism exalted the individual. Liberalism broadened its agenda to unify the two by harmonizing them.

Theological liberalism saw itself as the force to do it. Biblical Criticism had rescued the historical Jesus from the muck and mire of traditional orthodoxy. Romanticism then wanted to plant the idea of Jesus in the hearts of all people so they could become all their potential made possible.