This is the second episode in which we look at English Puritanism.

We left off last time with King Charles I fleeing London after breaking into The House of Commons to arrest the Puritan members of Parliament he accused of treason. The men had been warned and had fled. What Charles had hoped would be a dramatic show of his defense of the realm against dangerous elements, ended up being an egregious violation of British rights. So in fear for his own life, he packed up his family and headed out of town.

Back in London, John Pym, a leader of Parliament, ruled as a kind of king without a crown. The House of Commons proposed a law excluding the royalist faction of bishops in the House of Lords from Parliament. Other members of the House of Lords surprisingly agreed, so the clergy were expelled. This commenced a process that would eventually disbar anyone from Parliament who disagreed with the Puritans. The body took on an ever-increasing bent toward the radical. Feeling their oats, Parliament then ordered a militia be recruited. The king decided the time had come to respond with decisive action. He gathered loyal troops and prepared for battle against Parliament’s militia. Civil War had come to England.

Both sides began by building forces. Charles’ support came from the nobility, while Parliament found it among those who’d suffered most in recent royal shenanigans. Parliament’s army came from the lower classes, to which were added some from the emerging merchant middle-class, as well as a handful of those nobles who’d not been in favor at Court. The king’s strength was the cavalry, which of course was traditionally the noble’s military specialty. The Parliamentary forces strength was in their infantry amd navy, which controlled trade.

At the outset of the war, there were only minor skirmishes. Parliament sought help from the Scots, while Charles sought it from Irish Catholics. In its efforts to attract the Scots, Parliament enacted a series of measures leaning toward Presbyterianism. English Puritans didn’t agree with the Presbyterian plan for church government, but they certainly didn’t like the episcopacy of the Church of England’s royalist bishops. English Puritans ended up adopting the Presbyterian model, not only because it irked those Bishops, but because it made more Biblical sense at the time, and because confiscation of bishops’ property meant Parliament could fund the war without creating new taxes.

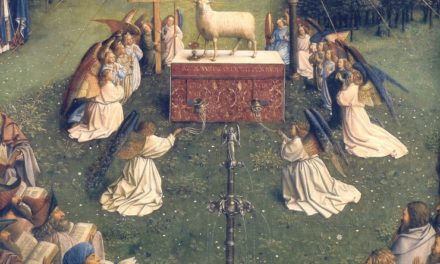

Parliament also convened a groups of theologians to advise it on religious matters. The Westminster Assembly included 121 ministers, 30 laymen and 8 Scottish representatives. Being that the Scots had the strongest army in Great Britain, though they numbered only 5% of the total participants in the assembly, their influence was decisive. The Westminster Confession which they produced became one of the fundamental documents of Calvinist orthodoxy. Although some of the Assembly’s members were Independents who followed a congregational-form of government, and others still leaned toward an episcopacy, the Assembly settled on a Presbyterian church government, and urged Parliament to adopt it for the Church of England. In 1644, Parliament joined the Scots in a Solemn League and Covenant that committed them to Presbyterianism. The following year the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, was executed on the order of Parliament.

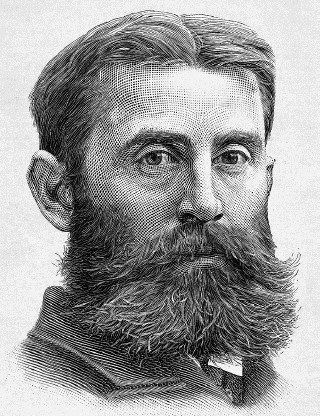

As Parliament built up its army, Oliver Cromwell came to the fore. A relatively wealthy man, he descended from one of Henry VIII’s advisors. Oliver was a devoted Puritan, convinced that every decision, both personal and political, ought to be based on the will of God as revealed in Scripture. Though he was often slow in coming to a decision, once set upon a course, he was determined to follow it through to its conclusion, believing it to be, in fact, God’s Will. Respected by fellow Puritans, until the Civil War he was simply known as a member of the House of Commons. But when he was convinced armed conflict was inevitable, Cromwell returned home where he recruited a cavalry corps. He knew cavalry was the king’s main weapon, and that Parliament would need their own. His zeal was contagious, and his small force accomplished great deeds. They charged into battle singing psalms, convinced they were engaged in a holy cause. That attitude spread to the rest of the Parliament’s army which crushed the royal army at the Battle of Naseby.

That was the beginning of the end for the king. The rebels captured his camp, where they found proof he’d been asking foreign Catholic troops to invade England. Charles then tried to negotiate with the Scots, hoping to win them with promises. But the Scots took him prisoner and turned him over to Parliament. Having won the war, Parliament adopted a series of Puritan measures, including setting the precedent that Sunday was to be reserved for solemn religious observances rather than the frivolous pastimes increasingly being adopted by the English nobility and emerging middle-class.

The Puritans, who’ had to unite due to war, now returned to what they best at, arguing among themselves. Most of Parliament supported a Presbyterian form of church govt, which made for a national church without bishops. But the Independents who made up the majority of the army leaned toward congregationalism. They feared a Presbyterian church would begin to limit their ability to pursue their faith the way their conscience demanded. Tension grew between Parliament and the army.

In 1646, Parliament unsuccessfully tried to dissolve the army. Radical groups gained ground. A wave of apocalyptic fervor swept England, moving many to demand a transformation of the social order thru justice and equality. Parliament and the leaders of the Army began to square off with each other.

Then è The king escaped. He opened negotiations with the Scots, the army, and Parliament, making contradictory promises to all three. Somehow he managed to gain support from the Scots by promising to install Presbyterianism in England. When the Scots invaded, the Puritan army defeated them, captured Charles I, and began a purge of those factions in Parliament they deemed inconsistent with the reforms they envisioned. Forty-five MPs were arrested. What remained was labeled by its enemies the Rump Parliament because all that was left was the posterior of a real parliament.

The Rump Parliament began proceedings against Charles, accused of high treason and of having thrust England into a bloody civil war. The fourteen lords who appeared for the meeting of the House of Lords refused to agree to the proceedings. But the House of Commons carried on, and Charles, who refused to defend himself on the grounds his judges had no legal standing, was beheaded at the end of Jan, 1649.

Now, I’m sure someone’s likely thinking, “Is this Communio Sanctorum or Revolutions?” Yeah, this doesn’t sound much like CHURCH history. It’s more English History. So what’s up? Well, it’s important we realize the roll Puritanism and Presbyterianism played in this period of English history. The Reformation had a huge impact on the course of events in the British Isles.

Fearing the loss of their independence from England, the Scots quickly acknowledged Charles’ son Charles II, as their sovereign. And in the South, England descended into chaos among several factions all vying for power

That’s when Cromwell took the reins. He commandeered the Rump Parliament, stamped out a rebellion in Ireland and the royalists in Scotland. Charles II fled to the Continent.

When Parliament moved to pass a law perpetuating its power, Cromwell expelled the few remaining representatives, and locked the building. Seemingly against his will, Cromwell had become master of the nation. He tried to return some form of representative government, but eventually took the title Lord Protector. He was supposed to rule with the help of a Parliament that would include representatives from England, Scotland, and Ireland. In reality, the new Parliament was mostly English, and Cromwell was the real government.

He set out to reform both church and state. Given the time, his policies were fairly tolerant. Although he was an Independent, he tried to develop a religious system with room for Presbyterians, Baptists, and even advocates of episcopacy. As a Puritan, he tried to reform English society through legislation. These laws were aimed at keeping the Lord’s Day devoted to sacred rites, ending horse races, cockfights, the theater, and so on. His economic policies favored the middle-class at the expense of the nobility. Among both the very wealthy and the very poor, opposition to his rule, which is called the Protectorate, grew.

Cromwell retained control while he lived. But his dream of a stable republic failed. Like the monarchs before him, he was unable to get along with Parliament—though his supporters kept his opponents from taking their seats. Since the Protectorate was clearly temporary, Cromwell was offered the crown, but refused it, hoping to create a republic. In 1658, shortly before his death, in a move that seems politically schizophrenic, Cromwell named his son as his successor. But Richard was most definitely not his father. He resigned his post.

Parliament then recalled Charles II to England’s throne. This brought about a reaction against the Puritans. Although Charles at first sought to find a place for Presbyterians within the Church of England, the new Parliament opposed it, preferring a return to the bishops’ episcopacy. The Book of Common Prayer was reinstalled after being out of favor for several years, and dissenters were banned. But such laws weren’t able to curb the several movements that had emerged during the previous unrest. They continued outside the law until, late in that 17th C, toleration was decreed.

In Scotland, the consequences of the restoration were more severe. With the episcopacy reinstalled in England, the staunch Presbyterianism of the North was challenged anew. Scotland erupted in riot. Archbishop James Sharp, prime prelate of Scotland, was murdered. This brought English intervention in support of Scottish royalists. The Presbyterians were drowned in blood.

On his deathbed, Charles II declared himself a Catholic, confirming the suspicions of many that he’d been an agent of Rome all along and thus all the blood of Puritans and Presbyterians. His brother and successor, James II, moved to restore Roman Catholicism as the official religion of his kingdom. In England, he sought to gain the support of dissidents by decreeing religious tolerance. But the anti-Catholic sentiments among the dissidents ran so strong they preferred no tolerance to the risk of a return to Rome. Conditions in Scotland were worse, for James II placed Catholics in positions of power, and decreed death for any who attended unapproved worship.

After three years under James II, the English rebelled and invited William, Prince of Orange, along with his wife Mary, James’s daughter, to take the throne. William landed in 1688, and James fled to France. In Scotland, his supporters held on for a few months, but by the next year, William and Mary were in possession of the Scottish crown as well. Their religious policy was tolerant. In England, tolerance was granted to any who subscribed to the thirty-nine Articles of 1562, and swore loyalty to the King and Queen. Those who refused, were granted tolerance as long as they didn’t conspire against the crown. In Scotland, Presbyterianism became the official religion of State, the Westminster Confession its doctrinal norm.

But even after the Restoration, the Puritan ideal lingered and greatly influenced British ethics. Its two great literary figures, John Bunyan and John Milton, along with Shakespeare, long endured among the most read of English authors. Bunyan’s most famous work, known by its abbreviated title Pilgrim’s Progress, became a hugely popular, and the subject of much meditation and discussion for generations. Milton’s Paradise Lost determined the way in which the majority of the English-speaking world read and interpreted the Bible.